Or that the top three museums in the world, the British Museum (est. 1753), the Louvre (est. 1793), and The Metropolitan Museum of Art (est. 1870) have never had female directors?

Or that only five women made the list of the top 100 artists by cumulative auction value between 2011-2016.

Men will argue that this is because most paintings in museums are historical and more men than women painted back then. Well, I think it’s safe to say that it’s not that more men painted, but that more men were allowed to paint. In 1723, Dutch painter Margareta Haverman was expelled from the Académie Royale when the painting she submitted was judged too good to have been done by a woman.

Since the 1700’s not much has changed for women artists. Marilyn Minter, however, refuses to let the sexism in the art industry hold her back.

During a time when people took photography about as seriously as they took women artists, Minter had the challenge of trying to make a living as both.

Offering a critical look at consumerism and the long standing abuse towards women by both men and capitalism, Minter made art critics and the public rethink their opinions on both photography and women artists.

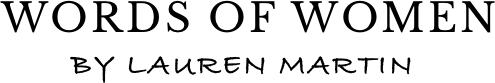

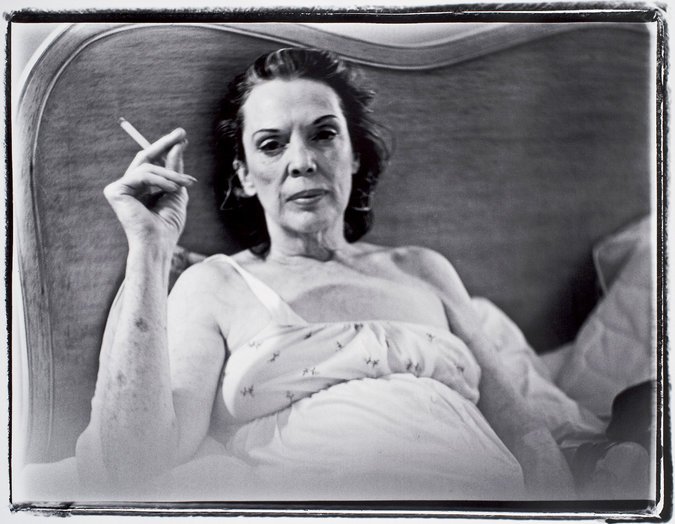

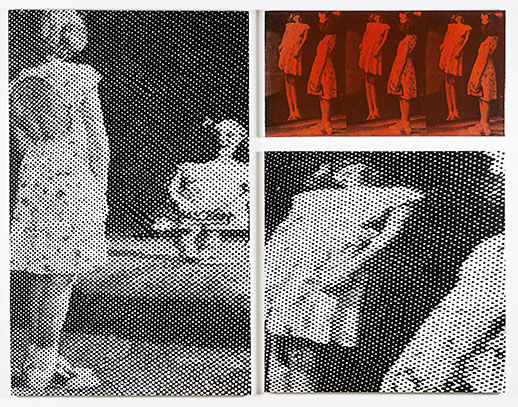

Born in Louisiana, Minter was raised in Florida. While still a student there, she created a series of photographic studies that involved her drug-addicted mother. (Those photos are now praised)

After earning a master of fine arts degree at Syracuse University, she moved to New York City where she started exploring pop-derived pictures often incorporating sexuality,

In 1989, at the age of 41, Minter created a series of works based on images from hardcore pornography based on the belief that nobody has politically correct fantasies. Minter thought that women should have sexual imagery for their own pleasure.

Reclaiming images from an abusive history, she asked the question, does it change the meaning if a woman uses these kinds of images. At the time this was a very complicated issue, and there were no simple answers. The timing was terrible as this was the pinnacle of political correctness.

One year later, Minter produced her first video “100 Food Porn”

This video was used as a television advertisement to promote her exhibition at the Simon Watson Gallery in New York. Minter used the gallery’s art advertising budget to buy 30 seconds on late night television in lieu of traditional print ad’s.

This was the very first commercial to advertise an artist’s show on late night television. She bought time slots on David Letterman, Arsenio Hall, and Nightline. (It cost $1,800 to buy a 30-second slot on David Letterman at that time.) “100 Food Porn” was shot and directed by NY documentary filmmaker Ted Haimes.

Through the 1990s she refined her works, which despite still having pornographic undertones, exuded a sense of glamour and high-fashion.

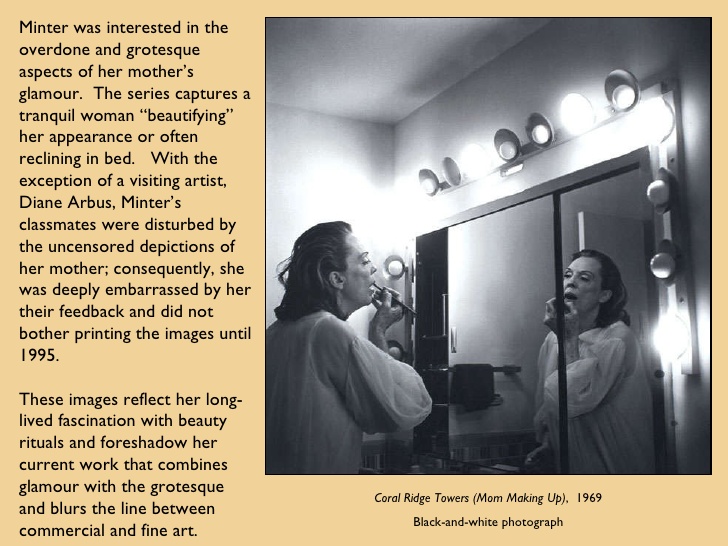

In 2006 Minter was featured in the Whitney Bienniale, and in a partnership with Creative Time, Minter was given ad space on four billboards in Manhattan’s Chelsea district. The billboards presented photographs of high heels kicking around in dirty water, and stayed up in Chelsea for a month.

Minter begins her process by staging photo shoots with film. She uses conventional darkroom processes. She does not crop or digitally manipulate her photographs. Her paintings, on the other hand, are made by combining negatives in photoshop to make a whole new image. This new image is then turned into paintings created through the layering of enamel paint on aluminum. Minter and her assistants work directly from this newly created digital image. The last layer is applied with fingertips to create a modeling or softening of the paintbrush lines.

Her art examines the relationship between the body, cultural anxieties about sexuality and desire, and fashion imagery.

Minter is best known for glossy, hyperrealistic paintings in enamel on metal that depict closeups of makeup-laden lips, eyes, and feet—a liquid-dripping gold-toothed smile or a pair of glistening high heels splashing in metallic fluid. Strut (2004–5) portrays a muddied foot in a gem-encrusted high heel.

According to Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, “From the beginning of her career, Minter has been embroiled in controversies over the relationship of her art to feminism, fashion, and celebrity. As her own profile as an artist interested in these vexed cultural intersections has grown, her work has risked looking as effortless as a mirror held up to the most supercilious aspects of today’s “bling” lifestyle. Yet Minter’s work is not merely a mirror of our culture, and this exhibition provides, for the first time, a critical evaluation of her practice as an astute interpretation of our deepest impulses, compulsions, and fantasies.”

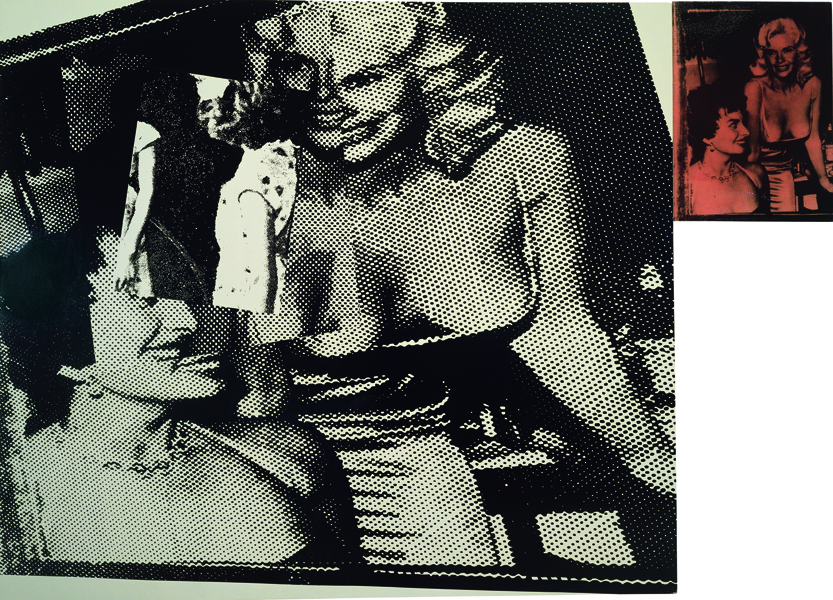

On the opposite end, her painting “Big Girls” combines the little girl gazing at her reflection with an appropriated image of Sophia Loren anxiously peering at Jayne Mansfield’s voluptuous figure spilling out of her dress. “These works, like the others from this period, fused a feminist critique of the construction of gender and femininity with other postmodernist hallmarks of the 1980s, including the appropriation of mass-media imagery translated in a cool, detached, style of painting,” says Elissa Auther, co-curator of the exhibition.

In every decade, Minter offers a smart woman’s critical look at issues that are otherwise presented by men for female consumption. The fashion world is full of male fashion house owners, designers, and photographers who create an image of being female. Rather than a blatantly naive critique of fashion, Minter shows the dual nature and slight imperfections of herself and her fellow woman, finding that true allure comes from the sensuality of imperfections. In one of her best-known paintings, Blue Poles (2007), Minter takes what is clearly a beautiful face and reveals flaws: a pimple, errant eyebrow hairs, and freckles. In real life these so called flaws make us human, attractive, and loveable, but in the beauty industry these imperfections need to be eradicated. In the age of Photoshop, where things such as freckles disappear from fashion and entertainment magazines, this painting can be understood as marking a final celebration of the attractiveness of the un-retouched human face.