Judy Chicago is an American feminist artist, art educator, and writer known for her large collaborative art installation pieces which examine the role of women in history and culture. Born in Chicago, Illinois, as Judith Cohen, she changed her name after the deaths of both her father and her first husband, choosing to disconnect from the idea of male dominated naming conventions. By the 1970s, Chicago had coined the term “feminist art” and had founded the first feminist art program in the United States. Chicago’s work incorporates stereotypical women’s artistic skills, such as needlework, counterbalanced with stereotypical male skills such as welding and pyrotechnics. Chicago’s most well known work is “The Dinner Party”, which resides in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum.

As Chicago made a name for herself as an artist, and came to know herself as a woman, she no longer felt connected to her last name, Cohen. This was due to the late grief of the death of her father and the lost connection to her name through marriage, Judith Gerowitz, after her husband’s death. She decided she wanted to change her last name to something independent of being connected to a man by marriage or heritage. During this time, she married sculptor Lloyd Hamrol, in 1965. (They divorced in 1979.) Gallery owner Rolf Nelson nicknamed her “Judy Chicago” because of her strong personality and thick Chicago accent. She decided this would be her new name, and sought to change it legally.

Red flag by Judy Chicago (1971)

Chicago was described as being “appalled” by the fact that she had to have her new husband’s signature on the paperwork to change her name legally. To celebrate the name change, she posed for the exhibition invitation dressed like a boxer, wearing a sweatshirt with her new last name on it.She also posted a banner across the gallery at her 1970 solo show at California State University at Fullerton, that read: “Judy Gerowitz hereby divests herself of all names imposed upon her through male social dominance and chooses her own name, Judy Chicago.” An advertisement with the same statement was also placed in Artforum’s October 1970 issue.

In 1970, Chicago decided to teach full-time at Fresno State College, hoping to teach women the skills needed to express the female perspective in their work. At Fresno, she planned a class that would consist only of women, and she decided to teach off campus to escape “the presence and hence, the expectations of men.” She taught the first women’s art class in the fall of 1970 at Fresno State College. It became the Feminist Art Program, a full 15-unit program, in the Spring of 1971. This was the first feminist art program in the United States.

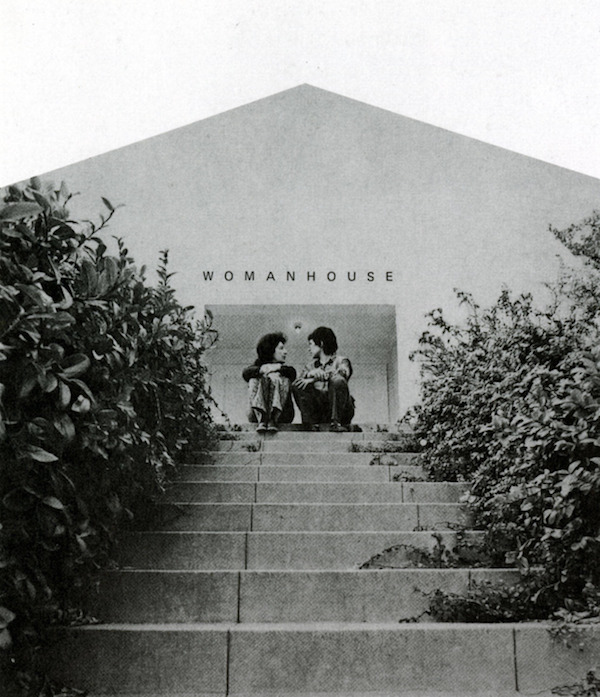

Miriam Schapiro and Judy Chicago outside of Womanhouse, 1971

Chicago became a teacher at the California Institute for the Arts, and was a leader for their Feminist Art Program. In 1972, the program created Womanhouse, alongside Miriam Schapiro, which was the first art exhibition space to display a female point of view in art. With Arlene Raven and Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, Chicago co-founded the Los Angeles Woman’s Building in 1973. This housed the Feminist Studio Workshop, described by the founders as “an experimental program in female education in the arts. Our purpose is to develop a new concept of art, a new kind of artist and a new art community built from the lives, feelings, and needs of women.” During this period, Chicago began creating spray-painted canvas, primarily abstract, with geometric forms on them. These works evolved, using the same medium, to become more centered around the meaning of the “feminine”.

From an interview with Huffington Post:

In your opinion, how has the position of female artists changed since you began your career? Has the art world changed in terms of its inclusion of female artists and feminist content?

Judy Chicago: Of course, I get asked this all the time. Here’s the good news; women artists (as well as artists of color) can be themselves in their work in ways that were unimaginable when I was young. And there are many more women and artists of color exhibiting. At the same time, at an institutional level (which is where my efforts have been aimed), there has been very little change.

What I mean is that art history is shaped by permanent collections, major solo exhibitions and monographs. Generally, women artists comprise less than 5% of permanent collections at major museums around the world. In terms of solo shows, between 2000-2004, 90% of the solo shows at the Met were white male artists. Between 2000-2005, both the Tate Modern and LA County Museum of Art presented solo shows of women artists less than 2 percent of the time. As to monographs on women artists, in the 1970’s, only one-half of one percent of art books dealt with women. More recently, it is 2.7 percent. So you tell me how much real change there has been.

Chicago was strongly influenced by Gerda Lerner, whose writings convinced her that women who continued to be unaware and ignorant of women’s history would continue to struggle independently and collectively.

Chicago decided to take Lerner’s lesson to heart and took action to teach women about their history. This action would become Chicago’s masterpiece, The Dinner Party, now in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum. It took her five years and cost about $250,000 to complete. Each place setting commemorates a historical or mythical female figure, such as artists, goddesses, activists and martyrs. The project came into fruition with the assistance of over 400 people, mainly women, who volunteered to assist in needlework, creating sculptures and other aspects of the process.

Subsequently, despite art world resistance, it toured to 16 venues in 6 countries on 3 continents to a viewing audience of 1 million. Since 2007 it has been on permanent exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, New York City, United States of America.

Below are some of the best quotes from Judy Chicago along with a video of her and Suzanne Lacey discussing the “Woman’s House” and feminism in the 70s and how it’s relevant today:

“As with Kahlo, there has been a tendency with O’Keeffe to view her work through the lens of her life story and relationship to a man, something that rarely happens with male artists. For instance, imagine a biography that examined the career of Jackson Pollock in relation to the ups and downs of his marriage with fellow artist Lee Krasner- inconceivable, yet usually unquestioned with Kahlo and O’Keeffe.”

“A woman’s work cannot be perceived accurately and will never be perceived accurately until women are perceived accurately.”

“My study of history taught me that many women artists have been erased from history and one of my goals has been to overcome that erasure.”

“You shouldn’t have to justify your work.”